[High Dimensional Statistics] Uniform Laws of large numbers

References

- Yonsei univ. STA9104 : Statistical theory for high dimensional and big data

- High-Dimensional Statistics : A Non-Asymptotic Viewpoint, 2017, Martin J. Wainwright

Uniform laws have been investigated in part of empirical process theory and have many applications in statics. in contrast to the usual law of large numbers that applies to a fixed sequence of random variables, uniform laws of large numbers provide a guarantee that holds uniformly over collections of random variables. A goal of this post is to introduce tools for studying uniform laws with an emphasis on non-asymptotic results.

Summary about convergence

- Pointwise ConvergenceLet $(N, d)$ be metric space. For sequence of functions

$$ \begin{align} &f_n : A \longrightarrow N, \quad n =1, \cdots , n \\ &f\,\,\, : A \longrightarrow N \end{align} $$ The sequence of functions are said to converge pointwise to the function $f$, if for each $x \in A$, $f_n (x) \longrightarrow f(x)$,

i.e. for each $x\in A$ and $\epsilon >0$, $\exists L = L(x, \epsilon)$ such that $d(f_n (x), (x)) \leq \epsilon , \quad \forall n \geq L$

- Unform Convergence

Let $(N, d)$ be metric space. For sequence of functions

$$ \begin{align} &f_n : A \longrightarrow N, \quad n =1, \cdots , n \\ &f\,\,\, : A \longrightarrow N \end{align} $$ The sequence of functions are said to converge pointwise to the function $f$, if for each $x \in A$, $f_n (x) \longrightarrow f(x)$,

i.e. for each $x\in A$ and $\epsilon >0$, $\exists L = L( \epsilon)$ such that $d(f_n (x), (x)) \leq \epsilon , \quad \forall n \geq L$

,which is same with

$$ \underset{x \in A} {sup} \quad d(f_n (x) , (x)) < \epsilon, \quad \forall n \geq L $$ - some relations

1. The derivatives of a pointwise convergent sequence of functions do not have to converge.

consider $X = \mathbb{R} $ and $f_n (x) = \frac{1}{n} sin(n^2 x)$ . Then,

$$ \underset{n \rightarrow \infty}{lim} f_n (x) = 0 $$ So, the pointwise limit function is $f(x)=0$; the sequence of functions converges to 0. What about the derivatives of the sequence?

$$ f_n '(x) = n cos (n^2 x) $$ and for most $x \in \mathbb{R}$, above derivative is unbounded, which means that it does not converge.

2. The integrals of a pointwise convergent sequence of functions do not have to converge.

Consider $X= [0,1],$ and $f_n (x) = \frac{2 n^2 x}{(1+n^2 x^2)^2}.$ Then,

$$ lim_{n \rightarrow =\infty} f_n (x) = 0 $$ However, the integrals are

$$ \int^1_0 \frac{2 n^2 x dx}{(1+n^2 x^2)^2} \overset{u = 1+ n^2 x^2}{=} \int ^{1+n^2}_{1 }\frac{du}{u^2} = 1 - \frac{1}{1+n^2} $$ Therfore, even thought $lim_{n \rightarrow =\infty} f_n (x) = 0$ for all $x \in X$, the intergral is 1 as $n \rightarrow \infty$

3. The limit of a pointwise convergent sequence of continuous functions does not have to be contuniuous

$A = [ 0, 1]$ and $f_n(x) = x^n $. Then,

$$ \underset{n \rightarrow \infty}{f_n (x)} = f(x) = \cases{0 \quad (0 \leq x <1)\\ 1 \quad (x=1)} $$

It satisfies pointwise convegence, but limit is not continuous

4. The uniform convergence implies pointwise convergence, but not the other way around.

Same example with above one.

If $f_n(x)$ converges uniformly, then the limit function must be $f(x) =0$ for $x \in [0,1)$ and $f(1) = 1$. Uniform convergence implies that for any $\epsilon >0 $ there is $N_\epsilon \in \mathbb{N}$ such that $\vert x^n - f(x)\vert$ for all $n \geq N_\epsilon$ . Then, consier $\epsilon = \frac{1}{2}$. Then, there is $N $ such that for all $n \geq N$, $\vert x^n - f(x) \vert < \frac{1}{2}$. If we choose $n=N$ and $x = (\frac{3}{4})^N$, $f(x) = 0 $ and thus

$$ \vert f_N (x) - f(x) \vert = \frac{3}{4} $$

contradicting our assumption.

1. Motivation

1.1. Almost sure convergence

Before start of demonstration, I will talk about two probabilistic convergence, Almost sure convergence and Convegence in probability .

1.1.1. Convergence in probability

For $X_n $ and $X$ on ($\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mathbb{P}$), A sequence of random variables converges in probability to a random variable X, denoted by $X_n \overset{P}{\rightarrow} X $ if

\[\underset{n \rightarrow \infty } {lim}\mathbb {P} (s \in S : \vert X_n(s) - X(s) \vert <\epsilon) \rightarrow 1 , \quad \forall \, \epsilon >0\],where $S$ is an underlying sample space.

1.1.2. Almost sure convergence

For $X_n $ and $X$ on ($\Omega, \mathcal{F}, \mathbb{P}$), A sequence of random variables converges almost surely to a random variable X, denoted by $X_n \overset{a.s.}{\rightarrow} X $ if

\[\mathbb {P} (s \in S :\underset{n \rightarrow \infty } {lim} \vert X_n(s) - X(s) \vert <\epsilon) \rightarrow 1 \quad\longleftrightarrow \quad \sum_{n=1}^\infty I(\vert X_n (s) - X(s) \vert >\epsilon ) < \infty , \quad \forall \, \epsilon >0\],where $S$ is an underlying sample space.

Here, second inequality is true by Borel- Cantelli lemma.

1.1.3. Comparison of concepts

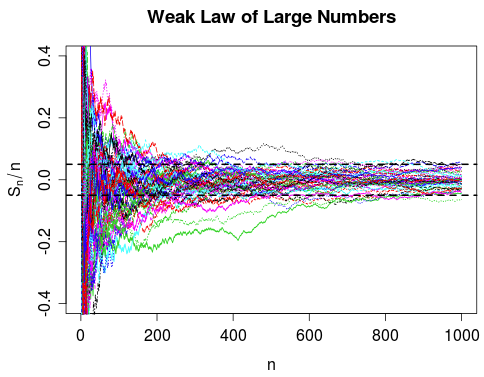

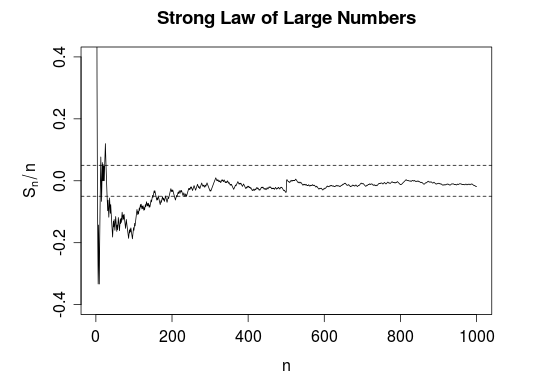

To understand the difference, Law of large number is one example.

I referred random variable - Convergence in probability vs. almost sure convergence - Cross Validated (stackexchange.com) for explanation here.

Weak law of large numbers, which states about convergence in probability of $\bar{X} = \sum_{i=1}^n X_i /n$, says that a large proportion of the sample paths will be in the bands on the right-hand side, at time $n$. It just means that the probability that particular curve to be located in curve will approaches to one.

However, in case of strong law of large numbers, a curve surely will be in bands.

The difference also can be seen from other representations of definition.

SLLN

\[\mathbb {P} (s \in S :\underset{n \rightarrow \infty } {lim} \vert X_n(s) - X(s) \vert <\epsilon) \rightarrow 1 , \quad \forall \, \epsilon >0 \quad \longleftrightarrow \underset{n \rightarrow \infty } {lim} \mathbb {P} (s \in S :sup_{m \geq n}\vert X_n(s) - X(s) \vert >\epsilon) \rightarrow 0 , \epsilon >0\]WLLN

\[\underset{n \rightarrow \infty } {lim}\mathbb {P} (s \in S : \vert X_n(s) - X(s) \vert >\epsilon) \rightarrow 0 , \quad \forall \, \epsilon >0\], $X_n = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n X_i}{n}$ in case of law of large numbers.

1.2. Cumulative distribution functions

Let $X$ be a random variable with its cumulative distribution function, $F(t) = \mathbb{P}(X \leq t), \quad \forall t\in \mathbb{R}$. Then, natural estimate of $F$ is the empirical CDF given by,

\(\hat{F}_n (t) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^nI_{(-\infty, t\rbrack}(X_i)\) Here, empirical CDF is unbaised estimator for pupulation CDF because

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E} [I_{( -\infty, t\rbrack}(X)] &= P(X \leq t) \times 1 + P(X \geq t) \times 0 \\ &= F(t)\\ \end{align}\]Moreover, uniform convergence of CDF is proved by Glivenko-Cantelli Theorem.

Uniform convergence is important because many estimation problem start from functional of CDF. For example,

- Expectation Functionals

which is estimated by plug-in estimator given by $\gamma_g(\hat{F_n}) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n g(X_i)$

- Quantile functionals

which is estimated by plug-in estimator given by $Q_\alpha (\hat{F}_n) = \inf { t\in \mathbb{R} : \hat{F(t)} \geq \alpha }$

Above estimators are justified by continuity of a functional. That is, once we know that $\lVert\hat{F_n} -F \rVert_{\infty}$ $\rightarrow $ 0 in probability, then we also have the result that $\vert \gamma( \hat{F_n} ) - \gamma(F) \vert \rightarrow 0$ for a functional $\gamma$, whenvert $\gamma$ is a continuous with respect to the sup-norm : $\lVert F- G \rVert_{\infty} = sup_{t\in \mathbb{R}} \vert F(t)- G(t) \vert$

continuous with respect to the sup-norm

we say that the function $\gamma$ is continuous at $F$ in the sup-norm if, for all $\epsilon >0$, there exists a $\delta >0$ such that $\vert \vert F-G \vert \vert _{\infty} \leq \delta$ implies that $\vert \gamma(F) - \gamma (G) \vert \leq \epsilon$.

1.3. Uniform laws for more general function classes

Let $\mathcal{F}$ be a class of integrable real-valued functions with domain $\mathcal{X}$ and let ${ X_i }_{i=1}^n$ be a collection of i.i.d. samples from some distribution $\mathbb{P}$ over $\mathcal{X}$. consider the random variable

\[\vert \vert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \vert \vert _{\mathcal{F}} = \underset{f \in \mathcal{F}}{sup} \bigg\vert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f(X_i) - \mathbb{E} [f(X)] \bigg\vert\],which measures the absolute deviation between the sample average and the population average, uniformly over the claff $\mathcal{F}$. we say that $\mathcal{F}$ is a Glivenko-Cantelli class for $\mathbb{P}$ if $ \vert \vert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \vert \vert _{\mathcal{F}}$ converges to zero in probability as $n \rightarrow \infty$.

- Empirical CDFs

We could see $\mathcal{F}$ satisfies the definition of Glivenko-Cantelli class by Glivenko-Cantelli Theorem. Therefore, $\mathcal{F}$ is Glivenko-Cantelli class

- Failure of uniform law

Not all classes of functionals are Glivenko-Cantelli. Let $\mathcal{S}$ be the class of all subsets $S$ of $\lbrack 0,1\rbrack $ such that the subset $S$ has a finite number of elements, and consider the function class $\mathcal{F}_S = { I_S (\cdot) : S \in \mathcal{S} }$ of indicator functions of such sets. Suppose that samples are drawn from continuous distributions over $\lbrack 0,1\rbrack $ such that $\mathbb{P}(S) =0$ for any $S \in \mathcal{S}$ . on the other hand, for any positive interger $ n \in \mathbb{N}$, the discrete set $S_n = { X_1 , \cdots, X_n }$ belongs to $\mathcal{S}$, and moreover, by definition of the empirical distribution, we have

\[\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n I_{S_n} (X_i) = 1\]Therefore, we conclude that

\[\lVert \mathbb{P} { _\mathcal{n}} - \mathbb{P} \rVert = 1-0 = 1\quad for\,\,\, every \,\,\,positive\,\,\, integer \,\,\,n\], and thereby $\mathcal{F}_\mathcal{S}$ is not a Glivenko-Cantelli class for continuous distributions.

1.4. Empirical risk minimization

- Suppose that samples are drawn i.i.d. according to a distribution $\mathbb{P}_{\theta^\star}$ for som fixed but unknown $\theta^\star \in \Omega$.

- A standard approach to estimating $\theta^*$ is based on minimizing a cost function $\mathcal{L}_\theta (X)$ that measures the fit between a parameter $\theta \in \Omega$ and the sample $X \in \mathcal{X}$.

- We then obtain some estimate $\hat{\theta}$ that minimizes the empirical risk defined as

One specific example is Maximum Likelihood Estimator.

- In contrast, the population risk is defined as

where expectation is taken over a samples $X \sim \mathbb{P}_{\theta^\star}$. The statistical question of interest is how to bound the $excess \,\,\, risk$:

\[E(\hat{\theta}, \theta^\star) = R(\hat{\theta}, \theta^\star) - \underset{\theta \in \Omega}{\inf} R(\theta, \theta^\star)\] Which is risk from estimor of empirical risk minimization and true unknown estimator is how small compared to pupulation risk.

For simplicity, assume that there exists some $\theta_0 \in \Omega$ such that $R(\theta_0, \theta^\star) =\underset{\theta \in \Omega}{\inf} R(\theta, \theta^\star)$

With the notation , the exess risk can be decomposed as

\[E(\hat{\theta}, \theta^\star) = \underbrace{\{ R(\hat{\theta}, \theta^\star)-\hat{R}_n (\hat{\theta} , \theta^\star) \}}_{T_1} + \underbrace{\{ \hat{R}_n(\hat{\theta}, \theta^\star)-\hat{R}_n ((\theta_0 , \theta^\star) \}}_{T_2} + \underbrace{\{ \hat{R_n} (\theta_0 , \theta^\star) - R(\theta_0, \theta^\star)\}}_{T3}\]By the definition of $\hat {\theta}$, $T_2<0$. For the $T_1$,

\[T_1 = \mathbb{E}_{X} [\mathcal{L} _\widehat{\theta}(X)\rbrack - \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n {\mathcal{L} _{\widehat{\theta}} (X_i)}\], uniform law of large numbers over the cost function $\mathcal{F}(\Omega) = { x \rightarrow \mathcal{L}_\theta (x), \theta \in \Omega_0 }$ is required. With this notation,

\[T_1 \leq \underset{\theta \in \Omega_0}{sup} \bigg\vert \frac{1}{n}\mathcal{L}_{\theta} (X_i) - \mathbb{E}_X [\mathcal{L}_\theta (X)]\bigg\vert = \vert \vert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \vert \vert_{\mathcal{F}(\Omega)}\]Also, for the $T_3$ , is dominated by this quantity,

\[T_3= \frac{1}{n} \sum \mathcal{L}_{\theta_0} (X_i) - \mathbb{E}_x \lbrack\mathcal{L}_{\theta_0} (X)\rbrack\]It is also dominated by above quantity,

\[E(\hat{\theta}, \theta^\star) \leq 2\vert \vert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \vert \vert_{\mathcal{F}(\Omega)}\]It states that the central challenge in analyzing estimators based on empirical risk minimization is to establish a uniform law of large numbers for the loss class $\mathcal{F}(\Omega)$.

2. A uniform law via Rademacher complexity

2.1. Definition of Rademacher complexity

- Empiricial Rademacher complexity of the function class $\mathcal{F}$

For any fixed collection $x_1^n = (x_1 ,\cdots ,x_n)$, consider the subset of $\mathbb{R}^n$ given by

\[\mathcal{F} (x_1^n) = \{ (f(x_1), f(x_2) , \cdots f(x_n )) : f \in \mathcal{F} \}\]The empirical Rademacher complexity is given by

\[\mathcal{R}(\mathcal{F}(x_1^n)/n) = \mathbb{E} _{\epsilon} \bigg\lbrack \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \epsilon_i f(x_i) \bigg\rbrack\], where $\epsilon_1, \cdots , \epsilon_n$ are $i.i.d.$ Rademacher random variables.

- Rademacher complecity of the function class $\mathcal{F}$

By taking expectation on empirical rademacher complexity,

\[\mathcal{R}(\mathcal{F}) = \mathbb{E} _{X,\epsilon } \bigg\lbrack \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \epsilon_i f(x_i) \bigg\rbrack\] By the form of formula, note that the Rademacher complexity is the maximum correlation between the vector $(f(x_1), f(x_2) , \cdots f(x_n ))$ and the noise vector ($\epsilon_1, \cdots , \epsilon_n$). Also, if a function class is extremply large, then we can always find a function that has a high correlation with a randomly drawn noise vector. Conversely, if function size is too small, correlation will be small.

In this sense,the Rademacher complexity measures the size of a function class and it plays a key role in establishing uniform convergence resuts.

2.2. Glivenko-Cantelli propety

- $Define)$ a function class $\mathcal{F}$ IS $b$-uniformly bounded if $\vert \vert f \vert \vert_{\infty} \leq b$ for all $f \in \mathcal{F}$.

- Theorem (Glivenko-Cantelli property) For any $b$-uniformly bounded class of function class $\mathcal{F}$ , any positive integer $n \geq 1$ and any scale $\delta \geq0$, we have

with $\mathbb{P}$ -probability at least $ 1 - \exp \big( -\frac{n \delta^2}{ 2 b^2 }\big)$. Consequently, as long as $\mathcal{R}_n(\mathcal{F}) = o(1),$ we have $\vert \vert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \vert \vert _{\mathcal{F}} \overset{a.s.}{\rightarrow} 0 $.

proof)

- Borel-Cantelli lemma

Let $\epsilon >0$ and define

\[A_n (\epsilon) = \{ s \in S : \lvert X_n (s) - X(s) \rvert \geq \epsilon \}\]Borel-Cantelli lemma says that if $\sum_{i=1}^\infty \mathbb{P}(A_n (\epsilon))< \infty, \quad then \quad X_n \overset{a.s.}{\rightarrow} X$

For above case,

\[\mathbb{P} (A_n ) = Prob (\lVert \mathbb{P} _n -\mathbb{P} \rVert_{\mathcal{F} } \geq 2 \mathcal{R}_n (\mathcal{F}) + \delta ) < \exp \bigg( -\frac{n \delta^2}{2b^2} \bigg)\]Therefore, since $\sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \exp \bigg( - \frac{n \delta^2}{2b^2} \bigg)< \infty$, the Borel-Cantelli lemma guarantees $\lVert \mathbb{P} n -\mathbb{P} \rVert{\mathcal{F} } \overset{a.s.}{\rightarrow} 0$ from the statement. Accordingly, the remainder of the argument is devoted to proving the inequality,

\[\vert \vert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \vert \vert _{\mathcal{F}} \leq 2 \mathcal{R}_N (\mathcal{F}) + \delta\]which will lead to uniform convergence of CDF .

- Step 1) concentration around mean

Let’s say that $\lVert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \rVert _{\mathcal{F}} := G(X_1 , \cdots , X_n)$. Then, to show the concentration around the mean, I will show the bounded difference condition of $G$ with $\max L_i \leq \frac{2b}{n}$.

\(\begin{align}

& \quad\,\,\bigg\lvert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n{\bigg( G(X_1 , \cdots, X_n)} - \mathbb{E}\lbrack{G(X_1 , \cdots, X_n)}\rbrack\bigg) \bigg\rvert - \underset{G \in \mathcal{F}}{sup} \bigg\lvert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n{\bigg( G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n)} - \mathbb{E}\lbrack{G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n)}\rbrack\bigg) \bigg\rvert\\

&\leq \bigg\lvert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n{\bigg( G(X_1 , \cdots, X_n)} - \mathbb{E}\lbrack{G(X_1 , \cdots, X_n)}\rbrack\bigg) \bigg\rvert - \bigg\lvert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n{\bigg( G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n)} - \mathbb{E}\lbrack{G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n)}\rbrack\bigg) \bigg\rvert \\

&\leq \frac{1}{n } \bigg\lvert \sum_{i=1}^n{\bigg( G(X_1 , \cdots, X_n)} - \mathbb{E}\lbrack{G(X_1 , \cdots, X_n)}\rbrack\bigg) - \sum_{i=1}^n{\bigg( G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n)} - \mathbb{E}\lbrack{G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n)}\rbrack\bigg) \bigg\rvert \\

& \leq \frac{2b}{n } \quad \longleftarrow b-uniformly\,\,\, bounded\\

&\longrightarrow\quad sup \,\,\,on\,\,\,each\,\,\,side\\

& G(X_1, \cdots, X_n) - G(Y_1 , \cdots, Y_n ) \leq \frac{2b}{n}

\end{align}\)

Then, by McDiard’s theorem ,

\[\lVert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \rVert_{\mathcal{F} } - \mathbb{E} [\lVert \mathbb{P}_n - \mathbb{P} \rVert_{\mathcal{F} }] \leq t\]with probability at least $1- exp (- \frac{nt^2}{2b^2 })$.

- Step 2) Upper bound on the mean

Combining results, one can get given inequality.

3. Upper bounds on the Rademacher complexity

3.1. Polynomical discrimination

Definition ( Polynomial Discrimination)

A class $\mathcal{F}$ of functions with domain $\mathcal{X}$ has polynomial discrimination of order $\nu \geq 1 $ if, for each positive integer $n$ and collection $x_1^n = \lbrace x_1 , \cdots, x_n \rbrace$, the set

\[\mathcal{F}(x_1^n) = \lbrace (f(x_1), \cdots, f(x_n) ) : f \in \mathcal{F} \rbrace\]has cardinality upper bound as

\[card (\mathcal{F }(x_1^n)) \leq (n+1)^\nu\]The significance of this property is that it provides with a straightforward approach to controlling the empirical Rademacher complexity

3.2. Bound on the empirical Rademacher complexity

Suppose that $\mathcal{F}$ has polynomial discrimination of order $\nu$. Then, for all positive integers $n$ and any collection of points $x_1^n = (x_1 , \cdots, x_),$

\[\mathbb{E}_\epsilon \bigg \lbrack \underset{f\in \mathcal{F}}{sup} \bigg\lvert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \epsilon_i f(x_i) \bigg\rvert \bigg\rbrack \leq 2 D(x_1^n) \sqrt \frac{v log(n+1)}{n}\], where $D(x_1^n) = \underset{f\in\mathcal{F}}{sup }\sqrt{\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n f^2 (x_i) }$ is the $\mathcal{l}_2$ - radius of the set $\mathcal{F}(x_1^n)/\sqrt{n}$.

proof)

For any fixed vector $a = (a_1 , \cdots, a_n) \in \mathbb{R}^n$, the random variable $\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n \epsilon_i a_i$ is sub-Gaussian with variance proxy $\sigma^2 = \frac{1}{n^2} \sum_{i=1}^n a_i^2$ . Since $\mathcal{F}$ has polynomial discrimination of order $\nu$, there are at most $(n+1)^\nu$ vectors of the form $(f(x_1) , \cdots , f(x_n))$, and each such vector has $l_2$- norm bounded by

\[\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n f^2 (x_i) \leq D^2 (x_1^n )\]Therfore, the empirical Rademamcher complexity is upper bounded by the expected supremum of $(n+1)^\nu$ Rademacher variables, each with variance proxy at most $D^2 (x_1^n) /n$. Applying maximal inequality of sub-Gaussian, it yields that

\[\begin{align} \mathbb{E}_\epsilon \bigg \lbrack \underset{f\in \mathcal{F}}{sup} \bigg\lvert \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \epsilon_i f(x_i) \bigg\rvert \bigg\rbrack & \leq D(x_1^n) \sqrt \frac{2 log(2(n+1)^\nu)}{n} \\ & \leq 2 D(x_1^n) \sqrt \frac{v log(n+1)}{n} \end{align}\]- one of maximal inequality used here

Let $X_1 , \cdots , $ be zero-mean sub-Gaussian random variables with proxy $\sigma^2$

Then, $\mathbb{E} [ \underset{1\leq i \leq n} {max} \lvert X_i \rvert] \leq \sigma \sqrt{2 log (2n)}$

3.3. Glivenko-Cantelli theroem

Corlloary (Glivenko- Cantelli)

Let $F(t) = \mathbb{P} (X \leq t)$ be the CDF of a random variable $X$, and let $\hat{F}_n$ be the empirical CDF based on $n$ i.i.d. sample $X_i \sim \mathbb{P}$. Then, for all $\delta >0$ and $n \geq 1$,

\[\lVert F - \hat{F}_n \rVert_{\infty} \leq 4 \sqrt{ \frac {log (n+1)}{n}} + \delta\]with probability at least $1 - \exp \bigg( - \frac{n \delta^2}{2b^2} \bigg)$. Therefor, $\lVert F - \hat{F}_n \rVert _\infty \overset{a.s.}{\rightarrow} 0$

proof )

Because for a givne sample $x_1^n = (x_1 , \cdots ,x_n) $ and function class $\mathcal{F} = \lbrace I_{(-\infty , t \rbrack} (\cdot) : t \in \mathbb{R} \rbrace $, consider the set $\mathcal{F}(x_1^n ) = \lbrace f(x_1) , \cdots , f(x_n) : f \in \mathcal{F} \rbrace$. Because it only divides real line into $n+1$ parts, cardinality is $n+1$, which means that polynomial discrimination of order 1. Then, by the results above, given inequalities works.

3.4. Vapnik-Chervonenkis dimension

Above, we see that Polinomical discrimination is useful to find the upper bound. One of way to verify that a given function class has polynomial discrimination is via the thoery of VC dimension. Consider a function class $\mathcal{F}$ where each function $f$ is binary-valued, {0,1} for simplicity. Then the set $\mathcal{F} (x_1^n)$ has at most $2^n $ elements. (Of course, because each element has 2 possibilities).

Definition (VC dimension) Given a class $\mathcal{F}$ of binary-valued functions, we say that the set $x_1^n = (x_1 , \cdots, x_n)$ is shattered by $ \mathcal{F}$ if card($\mathcal{F}(x_1^n)) = 2^n$. The VC dimension $\gamma(F)$ is the $largest$ interger $n$ of which there is some collection $x_1^n = (x_1, \cdots ,x_n )$ of $n$ points that is shatter by $\mathcal{F}$.

- Example : Two-sided Intervals in $\mathbb{R}$

Consider the collection of all two-sided intervals over the real line – namely $\mathcal{S_{both}} = { (b,a \rbrack : a,b \in \mathbb \,\,\, such \,\,\,that \,\,\, b < a }$. The class $\mathcal{S} _ {both}$ can shatter any two distinct points. However, given three distinct points $x_1 < x_2 < x_3$, it is not possible to pick out the subset {$x_1, x_3$}, showing that the VC dimension $\nu (\mathcal{S}_{both}) = 2$.

- Sauer’s Lemma

Consider a set class $\mathcal{F}$ with the VC dimension $\gamma{(\mathcal{F}) < \infty}$. Then, for any $n > \gamma({\mathcal{F}})$, we have that

\(card (\mathcal{F} (x_1^n)) \leq (n+1)^{\gamma (\mathcal{F})}\)

3.5. Multivariate version of Glivenko-Cantelli

Theorem

Let $X_1, \cdots , X_n$ be $i.i.d.$ obesrvations frnom a distribution $P $ on $\mathbb{R}^d$ . let $F$ denot the multivariate cumulative distribution function of $P$, that is

\[F(\bf{x}) = \mathbb{P} (\bf{X \leq \bf{x}}), \quad \bf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d\]where for vectores $\bf{x} = (x_1, \cdots, x_d)$ and $\bf{y} = (y_1, \cdots, y_d)$ in $\mathbb{R}^d $ , $\bf{x} \leq \bf{y}$ means that $x_j \leq y_u$ for all $j=1, \cdots, d$. Let $\hat{F}_n$ denote the empirical CDF of $P$, i.e.

\[\hat{F}(\bf{x}) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n I(\bf{X}_i \leq \bf{x}), \quad \bf{x} \in \mathbb{R}^d\]Then,

\[\vert \vert \hat{F} (\mathbf{x}) - F(\mathbf{x}) \vert \vert _\mathcal{\infty} \leq 2 \mathcal{R}_n (\mathcal{F}) + \delta \leq 4 \sqrt{\frac{d log(n+1)}{n}} + \delta\], with probability at least $1- exp(- \frac{n \delta^2 }{2})$.

proof)

At first, class of indicator functions characterized by the class of sets $\mathcal{A} = { (-\infty , x_1] (-\infty , x_2]\times (-\infty , x_d],(x_1, \cdots, x_d \in \mathbb{R}^d)}$ has VC dimension $d$.

because $\mathcal{A}$ has VC-dimension $d$, apllying sauer’s lemma, for fixed $x_1^n$ , we haver

\[card(\mathcal{F} (X_1^n)) \leq (n+1)^d\], which means that $\mathcal{F}$ has polynomical discrimination of order $d$.

Because class $\mathcal{F}$ is 1-uniformly bounded (Because it is CDF), implement Glivenko-Cantelli property, for any positive interger $n \geq 1$ and any scale $ \delta \geq 0 $, we have

\[\vert \vert \hat{F} (\mathbf{x}) - F(\mathbf{x}) \vert \vert _\mathcal{\infty} \leq 2 \mathcal{R}_n (\mathcal{F}) + \delta \leq 4 \sqrt{\frac{d log(n+1)}{n}} + \delta\]with probability at least $1- exp(- \frac{n \delta^2 }{2})$, which is,

\[\mathbb{P} \bigg( \vert \vert F-\hat{F}_n \vert \vert_{\infty }\geq 4 \sqrt{\frac{d log(n+1)}{n}} + \delta \bigg) \leq exp(- \frac{n \delta^2 }{2})\]

Leave a comment